Bored of cultural lists and round-ups, but cherishing the thoughts and the writing and the lives of the people I care about, I invited a bunch of people to tell me about a sharp moment of ‘perceptual awareness’ that stuck out through the fog of a grim year. Here’s the first half of those contributions. We hope that you enjoy them.

James Vincent

It was just a conversation. And I mean that in the way one might say, “it was just an apple” or “it was just a tree.” It was something simple and familiar, but without which the world would not make sense. More specifically, it was the first time in years we’d spoken with clear air between us.

In the past, the wreckage had been too much. It happens sometimes, that one day you open the door and find every inch of your home filled by debris, so impenetrable and overwhelming that you simply walk way. Then, much later, you pick out a piece, maybe just a small one, and think: “I know where this goes.”

We didn’t talk about anything important that day. There were no revelations or insights, no accusation or promises. Yet it felt like we were two angels, the last in the world, strolling along a clifftop on a bright and windy day, and that it had been some time since the disaster.

Jennifer Soong

What I found out this year is that my life could be very good and very bad at the same time, and that often the bad things stayed, even when I cut the good things loose, because they themselves were turning bad. Things could feel muddled and then appear totally separate and unrelated, in that way. Responding to your generous prompt, Ed, I realize the thing that struck me most was the unrelentingness of this kind of presence. There can be such a thing as too much of it. Maybe writing is my way of trying to get rid of something by using it all up, but I learned this year that there are some things, like physical sensations, that can’t be sublimated or ejected like that.

Jethro Turner

At some point in the spring, in the depths of grief and a heartbreak, I stopped dreaming. Literally. It sounds like a metaphor like all the usual ones, like “the sky was less blue”. But actually I just stopped dreaming. I think I went to sleep at some points, but I didn’t do a lot of that either. And in the space between waking and sleep, I had vivid lucid dreams, giant shifting visual architectures like a scaffold for all the rushing thought. But I just couldn't dream if I tried. Not that you can.

By the end of the year, I was in Paris, riding the metro between gallery visits, well-slept and thinking things like “call me Saint-Placide”. I went back to the Musée de Cluny for the first time in about a decade to see a series of medieval tapestries called ‘The Lady and the Unicorn’ (La Dame à la licorne).

We become hyper aware of the movements of bodies in these near silent spaces. I sat down before going in to see the old Dame in an old cloisters, in front of some fragments of statues. They are on display with the missing parts illustrated behind, suggesting unbroken beauty, intimating wholeness. Perhaps like all of us.

In the dark room where they live, there are six tapestries: five of them each devoted to the senses, all moments of perceptual awareness. I settled perhaps for longest in front of the sixth, which is not. It is called ‘À Mon Seul Désir’.

Everything figurative floats in its rectangular space: flowers, fruit-laden trees, a monkey, hunting hounds, a lapdog, lambs and rabbits. The lady, her female servant, and some of her coterie of beasts also seem to hover on a platform of bright vegetation. Above them, what seems to be a heron, is pursued by a domesticated falcon, its jesses dangling in the non-air.

The only words on any of these works are ‘À Mon Seul Désir’, emblazoned on the tent behind the lady (its entrance held open by a lion and the unicorn). I looked it up on Wikipedia as I sat there, which told me that ‘It is variously interpreted as "to my only/sole desire", "according to my desire alone", "by my will alone", "love desires only beauty of soul", and "to calm passion"’.

A gang of kids interrupts the writing of this as I sit in the public library. They are boys and they must be about 12 or 13, that age when girls have become serious and hilarious amounts of hormones are coursing through your veins, and you play games where you all pretend to all be asleep, snoring loudly in the library until the security staff come and shout at you and chase you off. Which is what happens.

Katie Ebbitt

I gave blood in the morning. I walked off the street and into the municipal building. Went through the metal detector and up to the top floor with panoramic views of New York City. I was newly in love and thinking about the past love which had brought me into existence. My grandparents were born, met, lived, and died on the same small lake in Michigan. Both donated pints of blood equaling gallons. I was registered with the nurse, and placed on a bed, playing Duolingo beside a cop, fireman, government worker. Another cop. I was asked to give my profession. “Social Worker.” The blood came out fast. I got off the table. I left before the observation period was over. Walked the mile westward home. Later that day, just before night, I got off a train in Brooklyn and encountered a small creature fragile in the middle of the sidewalk. Convinced it was a squirrel kit, I picked up the infant animal, forgoing the evening’s plans, and went home. I expected the creature to die during the night, as small things so often do. But the baby lived, hydrated by sugar water. In a shoebox, we rode Uptown to the wild animal rehab. "One second," they said at the door, "this may not be a squirrel." Rat Reddit helped me to raise my friend for the next three weeks, its baby eyes opening, and ears unfurling. Its coat comes in brown. On the eve of my rat going to its permanent home to reside with a wild rat enthusiast, a professor of astrophysics at West Point, the creature disappeared from her cage. Little love going out and beginning some other life in my building’s walls. The way that we all crawl away from our families.

Lamorna Ash

I was going to tell you about seeing moon-made shadows for the first time in a forest on America’s east coast, or the single solitary minute out of the millions of minutes I must have spent inside my current flat during which no cars passed by on the main road below us; I thought I might explain how amazed and how unlike ourselves we all felt for that brief moment of spectacular silence. Those were both experiences that jolted me out of orbit this year – only for a few seconds, but that’s all you’re asking for, and all I ask for myself so as to prevent all my days from congealing into one meaningless, undifferentiated substance. But then there was this one other example from this year, which felt so highly pitched that I would swap out a hundred small alternative experiences of renewed attention or awareness just to feel it again. How can this be the case but it is in fact the case that until this year I thought I was someone fated never to experience a shattering, full-blown, knock your socks off orgasm – that I had one of those faulty bodies which could only reach a sort of long nice plateau of pleasure. It took thirty years but it was worth it and I doubt anything better will happen to my body in cahoots with my mind this year, or next year, personally.

Matthew Holman

On Seeing Louise Giovanelli’s ‘Entheogen’ (2023):

Perhaps mostly for reasons of hygiene or simply ease of jaw, it’s rare that we keep our mouths open for longer than we need to. Rarely more than a few seconds. We speak, we eat, we kiss, and then we purse our lips back together. Maybe you’re in a community choir, I guess, or maybe you speak in tongues. It can be striking, then, to find a contemporary picture of a young woman with her mouth wide open and held there in stasis by the thinned materiality of a painting. I see her: she’s awash in Scheele’s green, like arsenite, like neon, as though it’s projected onto her face from an exterior light source. Her eyes are hard closed, her mouth agape. Our lady in green has cropped eighties fringe, clearly elsewhere, in another place, in another time. I wrestle with the idea that we hold our mouths open for extended periods of time only in those scarce moments when we feel released from the threat of shame that otherwise we are always guarding against with a heightened sense of composure. I guess it’s our hyper-sexualised age, amongst other things, that makes me believe our lady in green is enraptured in the throes of orgasmic abandon. But what if she is merely waiting to consume the blood and body of Christ?

Misha Honcharenko

My year beckoned anticipation, a strong tremor by virtue of continuation living after wounds of the past years. War in Ukraine, caretaking, mother’s death, losing friends due to war, ongoing genocide in Palestine and Lebanon, world collapsing. This certain feeling of horror did not leave me. Due to the interrupted end of life. Relocation to West Yorkshire from Cork, from Ukraine. Instant—was the first trip to London, albeit alone or with someone, just rubbing my feet until they bleed considering the shoes I bought are unbearable. The beauty was the air of sudden homesickness. Regarding delineations of love for a mother that I can no longer see. Made me feel electrified, to be in love, to be needed, also that my body is able to revive. Paralysis—that carried me back to Yorkshire. This is my next stop, open mouth said.

Molly Pepper Steemson

It is easy to make a fennel salad.

At the start of the year, at the start of our relationship, when we were hungry for one another in that relentless, insatiable, untenable way, we worked from home together. It was cold and sunny and I made lunch.

Five eggs, boiled—two each, one to share; toast, buttered; fennel salad. I sliced the fennel on his mandoline, which was the same pale green as mine—like the colour where the frond meets the bulb. We ate outside.

I have made more fennel salads since. With soft herbs and without, with shallots, with capers, lemon zest, lemon juice, no olive oil at all (I forgot). It is a side dish, a snack, a little lunch. There is often a browning bulb of fennel in the fridge, that can be revived by pulling off its outer layer.

My new relationship is not so new. We have arguments, we have sex, we have lunch—a fennel salad.

Richard Porter

Standing on the shore as winter darkness fell with the waves crashing and a lighthouse in the distance and some kind of rig at sea possibly something to do with the nuclear power station emitting its strange red light as if some visiting spacecraft floated there soon to depart and everything around it squeezed of blue into grey into black but for a tiny silhouette of a man and his dog who on passing said “looks like a storm coming” and disappeared

Roisin Agnew

The first time I drove on my own I went to a portion of the lakefront, pulled in, parked, and got out. It wasn’t a particularly scenic part of the lake or a place that held any sentimental value to me. It was late afternoon in early May, a few stray cars, two men with fishing rods, a “foreigner” wading into the cold water, but mostly it was quiet, too early in the season. I had done this road a thousand times, but now it was as though it were a place I’d never been to before. I had got myself there and I could get myself out of there whenever I wanted. I looked at the lake until I noticed that the bus I had parked next to wasn’t empty and that the driver was staring at me from under his sunglasses. I got back in and drove home, elated.

I got my driving licence in London this year. I had done driving lessons and taken tests in three countries (Italy, Ireland, Britain) over almost 15 years and given up or failed at different times. When I finally passed in March of this year it was thanks to Amdi, a forbidding Kosovan driving instructor I’d inherited from my friend Orlando, who I was often compared to unfavourably. Amdi was determined I would pass because he couldn’t bear to keep teaching me, he said. His main way of interacting with me was to point out mistakes I’d made by asking rhetorical questions. When I’d sheepishly give the obvious answers he would bellow, “Thank Godz!” I loved Amdi.

There are very few material markers of my independence and hard work despite how real they are. I don’t own a house, I don’t have children, I don’t earn a high income. Getting my driving licence took on an outsized importance and urgency, maybe something to do with the new-found price I put on my autonomy or maybe just because I’ve always loved driving.

This week I experienced my first Rome traffic jam. I spent forty minutes making my way around Castel Sant Angelo, the star-shaped medieval residence of the pope, a drive that would normally take a minute. It was not unusual, construction work for the jubilee has made it one of Rome’s severest bottlenecks, but I felt giddy sitting in my car alongside other drivers. I had got myself there and I could get myself out of there.

(Photo by Roisin)

Orlando Reade

Last winter, police tape appeared across the street that runs between my apartment and the studio where I write. Later, I read that a woman had been killed. An attempt on the life of her son had claimed hers instead. The article called her a pillar of the community.

The next day, the street was open again, and tape across one doorway identified where it had happened. A house with a back garden, out of which music had once floated on summer nights. Flowers, candles, and liquor bottles appeared on the wall outside.

One night, there was a car pulled up outside the house. The driver’s door was open, and a person – it could have been a man or a woman, I couldn't tell, or a boy – was standing in the gap between the door and the car. A ballad was playing on the stereo, and the person was rocking back and forwards. A private ceremony I had intruded upon.

Last week, there was a gathering outside the house, with music on a sound system. I guessed it was the first anniversary. ‘Candy’ by Cameo was playing, and people were turning in unison in the December rain. Seeing that made me cry.

Zoe Guttenplan

This gallery’s floors are polished concrete. The walls are vast. In the ceilings, high above, joists and beams map space, painted white as the heavens visible through the skylight. Pitched pains are perfectly clear, perfectly clean. We’re in the main room, which has been populated by moulded plastic chairs – not Monobloc, those cheap seats you are just as likely to find in Chicago’s greenly manicured front yards as on the side of a goat track just outside of Athens. These chairs are not diagnosable sameness or mass production. These are bespoke. Three sans serif letters, the gallery’s logo, have been stamped out of the back of every chair, as though a hot brand has plunged into plastic, melting the dead space away. In the front row, a woman leans back, crosses legs, lifts chin. She is nodding at the speaker who is winding up to tell a joke and her earrings are swinging in broad magenta circles. At the punchline, her laugh is cavernous and round in a room full of corners and hard edges. Her flesh, wrapped in purple gauze, presses through the holes, undulating.

A massive thanks to everyone who sent me something for this. Hopefully some more posts from me in 2025. Bis gleich — Ed.

Bored of cultural lists and round-ups, but cherishing the thoughts and the writing and the lives of the people I care about, I invited a bunch of people to tell me about a sharp moment of ‘perceptual awareness’ that stuck out through the fog of a grim year. Here’s the first half of those contributions. We hope that you enjoy them.

(Photo of '“I AM” READING ROOM by Adrian)

Adrian Dannatt

The end of April and we had already been out a month, nearing the end now, a final push to the ocean. We were following ‘The Darkest Line’, a road route or possibly just a long poem, devised by writer Josh Shoemake. Working with a geographer and supercomputer Josh had minutely plotted our journey across the USA to avoid all light, taking side streets and abandoned alleys, ancient rural tracks, ‘the America where even electricity does not dare venture.’

We began at Jekyll Island, Georgia and now we were pulling in at twilight to the base camp of Mount Shasta, California. There are no coincidences on such an occult route; I had always wanted to see Shasta and it happened to be right on the path of our obscure plot.

At 14,179 feet Shasta is a psychic nexus, one of a small number of global "power centers” according to those of us awaiting the Harmonic Convergence. Many have hunted here for a rumored branch of the Great White Brotherhood or climbed to find the hidden city, somewhere up in the eternal snows, of advanced beings from the lost continent of Lemuria. It was high on Shasta that Guy Ballard met by chance a mysterious stranger who revealed himself as Comte de Saint-Germain, the eternal wandering adventurer. And yes, thus was born the ‘I AM’ movement.

I woke at dawn. Across the street opposite our motel was the ‘I AM’ Reading Room, a tiny wooden house and peering through the windows I was just able to make out the shrine to ‘Our Beloved Ascended Master St. Germain’.

I walked up steep Orem, a mystic street name in itself, amongst sitting room lamps lit against the early morning. I carried on walking to the outskirts of this town and at the last houses I looked up to see now the sunrise on the freezing white mountain side, scudding cloud. It was so cold, so early and tomorrow we would at last reach the Pacific.

Al Anderson

On my birthday I got shellfish poisoning from the oyster shack at Borough Market. I didn’t comment on the translucent greenish film over the rock oysters from Colchester, nor their disconcerting stillness, nor the more general sense of foetid air that hangs over that market – where I worked for many years. This was because I was cognizant of a pleasant, innocent mood and didn’t want to throw off its equilibrium. The sickness tinkered at the seams of my perception under the cover of a hangover before my body commenced with projectile vomiting, which continued at regular intervals for the next nine hours. This led into a further three or so days of fever and sweating and shitting and puking. The last time I was so unwell was at seventeen, with swine flu. Interestingly, that was also when I watched Saló for the first time. Interesting because the week leading up to the rancid oysters I’d rewatched Pasolini’s Trilogy of life movies out of order, starting with The Canterbury Tales; possibly the most melancholic sex comedy ever put to screen. In ‘The Cook’s Tale’ Pasolini’s younger boyfriend, Ninetto Davoli (who was in the process of leaving him while they were filming) plays an affably grotesque, if likeable, rogue swindling and leching and fucking up around Borough Market circa 1971, which easily doubles up as a Medieval slum. At its worst, the fever rattled my sense of consciousness to such a degree that any sense of the ‘real’ and the ‘imaginary’ collapsed altogether. I had whole days where I would drift through a mid-twentieth century London playing a more ancient version of itself and I was a creature altogether more complicated and sophisticated than the one that sits at a laptop typing this. I felt like a sort of angel, like a consciousness incomprehensibly capacious, like many thousands of eyes. I would go to work, go meet my boyfriend for katsu curry on London Bridge, which in this world was a sort of horizontal Chungking Mansion over the river, I’d re-read Cities of the Red Night, my favorite novel at seventeen, I would befriend ruddy cheeked aristos and involve myself in some court intrigue. The flow of that reality would then fade into the milky sheen of sweat and smells clouding the large square windows next to my bed in Bow. The fever can be a kind of epistemology, I learnt. The closest I got to really understanding the Earth was in that state of frenzied corporeality, as it was processed through a deracinated mind. Even as I recovered, everything felt feverish, or drugged. I’m still not all there. Apparently it can take up to two months for the lining of your stomach to fully heal after shellfish poisoning. As the experts love to tell us, gut health is intrinsic to maintaining a sound mind. Pasolini was heartbroken filming The Canterbury Tales and its nominally light-hearted register is weighed down by a mannered, melancholic photography. The world received by the viewer is several worlds palimpsesting one another; nothing coheres, but it holds; like a sad mummer’s song, conjugated from centuries worth of things disappearing.

Alexandra Symons-Sutcliffe

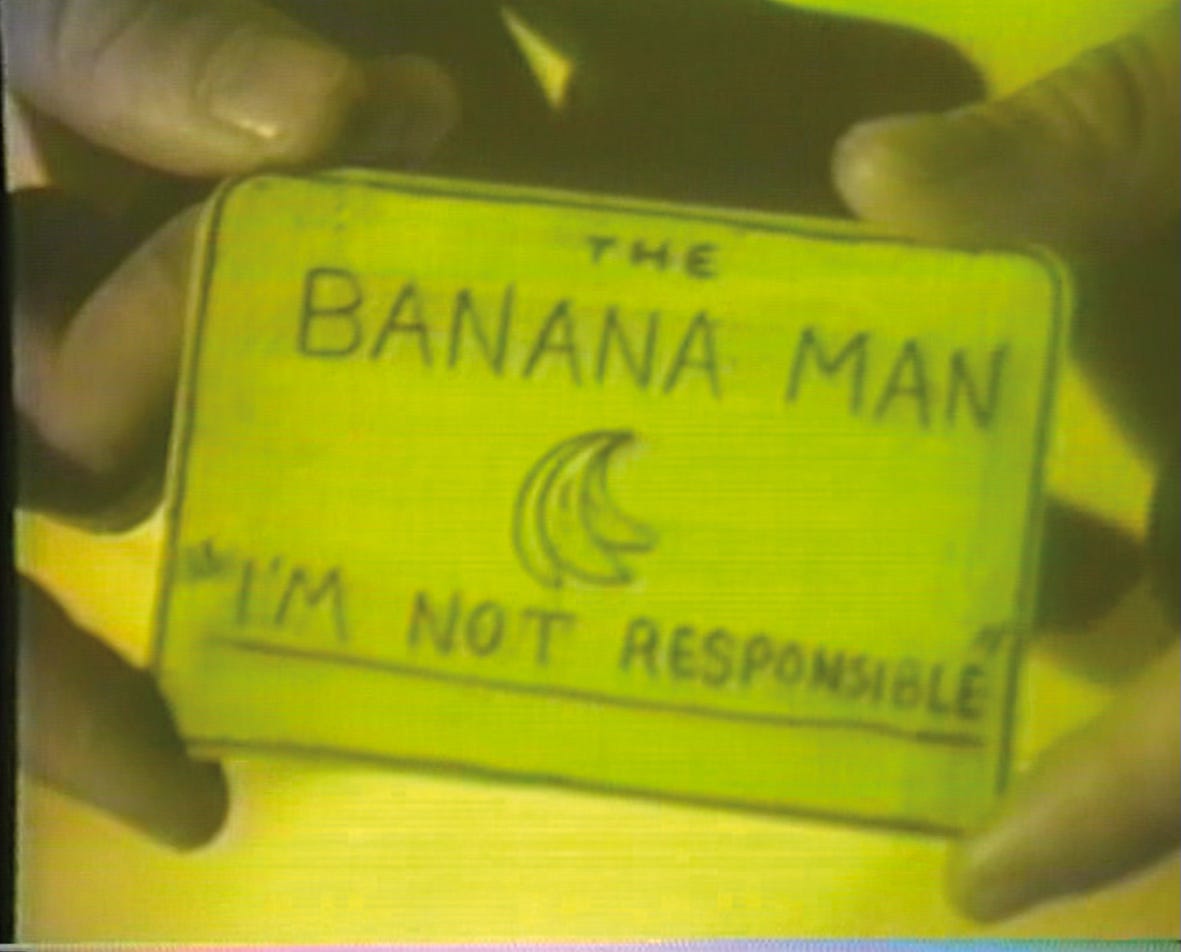

Included in Tate Modern’s current retrospective ‘Mike Kelley: Ghost and Spirit’, is Kelley’s first full video work The Banana Man (1983). The protagonist of the Banana Man is taken from a children’s television show that Kelley himself never saw but heard about from his classmates at school. Driven by a monologue, Kelley inhabits a persona who narrates their psychological motivation, detailing shame, rejection, and an urge for emotional independence. Dressed in a yellow sailor suit he cocks his head and turns down the corner of his mouth, a VHS-era Buster Keaton. He pulls a floppy appendage from the zipper of his trousers– boing!– swings it like a skipping rope that children jump in the playground. Spoken word and sound effects prefigure acted-out vignettes, a collage of signifiers contained within Kelley’s body, performed to the camera, which records and distances the viewer from liveness. Having no first-hand experience of the original show Kelley’s portrait is a double fiction, a TV character told through the interpretation of children Kelley hasn’t seen for decades.

If you know Mike Kelley you know how this one ends, and moving through the galleries you process towards his inevitable suicide. Not as a young man but in late middle age, when even bolstered by success and admiration he failed to continue to live. Kelley’s practice is laced with an obsessive, almost grotty, interest in the banality of American culture. Superman, high school architecture, sports rituals, and mass-produced toys… consumption habits re-interpellated as the material reality of our lives. We all know how this feels: a pop song you never liked plays on the radio at the wrong moment and suddenly it breaks your heart, a sexual position that mimics your partners’ previous partner’s taste in pornography, a schoolyard game seemingly invented anew by every generation of children, but in the exact same form it took in their parents’ day. Throw an object out in front of you and run towards it, you can't help but drag an assemblage of inherited trash behind you.

The final video work in the Tate show is ‘Bridge Visitor (Legend-Trip)’ (2004), which recalls the summer camp legends of cryptids that peppered Kelley’s adolescence. An aged naked figure, perhaps Kelley, lumbers towards the camera across a bridge but he never reaches the viewer. In the previous room, ‘The Banana Man’ plays on a loop. Twenty-nine when he made it, still younger than Jesus, dressed in an infantile costume, playing out juvenile memories, but not ones that belong to him. Kelley forever in a middle zone, a vector for the culture that surrounded him, and now a container for disappointments and diminishment of that same culture. Tragedy is emotionally effective because it de-privileges originality; a series of small failures that build into an inevitable disaster, foreseen from the very start. In ‘The Banana Man’ Kelley chases himself through a composite image of an interior world, rendered authentic through its repetition.

(Still from Mike Kelley’s ‘The Banana Man’)

Anu Kumar Lazarus

Why didn’t I throw you away?

Ugly (to others). Beautiful (to me).

You have been on my shelf for

is it 21 or 3 years now?

I can’t recall or make sense of it all

You are missing a lid, something broken?

There was a unique “twist and apply” mechanism

for the deep crimson colour

to paint in the parting of my hair every day

to celebrate our marriage.

But, I was allergic?

Or maybe an invisible fungus grew in the vermilion powder

And irritated me.

You were very inexpensive

From outside the

Sankat Mochan temple in Varanasi?

I was night shopping by gas light with my cousin and her son?

My husband was not there that time?

Anyway, now he is here, with me all the time

And certainly for longer than this squat pot

Which I must refresh.

So to lick the naked flesh of my scalp with a new scarlet tinge.

Asa Seresin

Responding to the zeitgeist, Anxiety is the star of Inside Out 2. Skinny and orange, with a mouth twice the width of her face stretched into a perma-grin, Anxiety is one of the new emotions induced by the film’s protagonist, Riley, going through puberty. She makes a show of being deferential to the brain’s girlboss, Joy, but secretly plans to dethrone her, finding her insufficiently paranoid for the demands of teenage life.

Predictably, Anxiety’s master plan for conquering contingency goes wrong, culminating in a sequence in which she takes over the brain’s control panel at such a manic speed it creates a tornado around her: a panic attack. The wind and music roar in what is initially the climax of “mild peril” typical of children’s film. But then the camera cuts to the inside of the whirlwind, and the music is silenced, and we see Anxiety frozen in place, glitching, arms splayed, eyes wide, physiologically forced to smile even as her face is electric with terror.

I am not an especially anxious person, but this scene undid me. I was moved less by Anxiety's particular choreography of strategizing and projecting, and instead the sudden silence: that frozen part, beneath our relational capabilities, that says No one can help me.

Inside Out 2 is the highest-grossing animated film in history, and my reaction to it is completely generic; on Reddit, scores of adult viewers, many of them middle-aged men, report responding in the exact same way. For me, this has been a year of turning away from the neurotic drive to originality and obscurity that characterizes academic life, and the cynical economy of microfame required by careers in the cultural sphere. Embracing a new level of basicness, I became obsessed with a furry heart with a smiley face my husband bought me on a whim from a stationary shop. (I think I have a constitutional oversensitivity to emojis.) On email and Whatsapp, I made it my profile photo.

Watch this film illegally. Disney+ subscriptions are on the BDS list (due to the latest Marvel Captain America film).

(Anxiety from Inside Out 2)

Danny Hayward

Dear Ed,

I’ve struggled for a week to think of something to say to you that I haven’t already said a hundred times already. In the end I realised I have to go back further than I have been accustomed to going.

When Marina received the diagnosis that her cancer had metastatised, in early 2021, and was beginning to understand for the first time that it would never go away, the first thing she said to me, after she had told me the news, was that she was worried about whether I would be OK. I remember where we stood in our bedroom in Wenlock Street, between the bed and the window, but I can’t remember what I said in reply.

When three years later she was dying in the Vienna General Hospital, and her doctors wanted me to convince her to give up on the idea of whole brain radiotherapy, because it would only make things worse, they took me out into the common area of the palliative care ward, and a grief counsellor made me cry, and I was angry with them for pushing me into it and I told them that I was only crying because until then Marina had always cared for me, as I had cared for her, that it had always been reciprocal, and it was only now, when her energy was gone and she was unable to stand up anymore, that I felt that I had to take care of myself.

And then I went back into the room and Marina asked me what they had told me, and I told her. And I wanted to try to say the most fundamental thing I could think to say to her that was true, and I told her that I would never be as close to anyone as I was to her, and she reached out to me with her arm to pull me closer and said she would love me long after she was gone.

Thinking about this now, I realise that the promise she made negated the anxiety I had just expressed about being finally on my own. I am so grateful to her for not releasing me. I cannot think of anything more painful than being released. This morning, in the Guardian, I read a review of a posthumous memoir by a woman dying of cancer, in which the editor said that once she finished working on the manuscript, her friend, the author, was ‘gone’. The idea of being released into non-relation is death to me. The survival of our relation means more to me than life; and the refusal to give up on relation is the point to which wherever I go now in my head I know I can return, that is ineliminable, and that makes it worth being alive.

Danny

Daisy Lafarge

2024 was the year in which increasing my consumption of a little white powder changed everything. Obviously I am talking about salt. Salted butter, salt on slices of apple, little sachets of electrolytes I carry everywhere I go. A plastic fish of soy sauce lifted from Itsu if things start getting wavy. I am a cow and the world is my mineral lick.

At the end of 2023 I finally got a diagnosis of something I’ve experienced since puberty, the effects of which I had normalised as part of my (terrible) personality, and which ex-partners have both kindly and unkindly diagnosed as autism, diabetes, BPD and OCD. It turned out to be PoTS – a dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, now famous thanks to its role in Long Covid. One symptom is an inability to tolerate changes in gravity – standing up will make your pulse go haywire, your blood drain away from your brain and pool in your feet. At best you’ll feel dizzy and low-key catatonic for a few hours; at worst you’ll faint.

Trying to manage this condition without knowing it was a condition has shaped my social existence in ways I am only just grasping. I was not aware that what I experienced were symptoms – I simply knew I had to abandon social events when and if, and that in the end it was always easier to be alone, to not have to try and locate a what and why. It was both a relief and kind of pitiful to realise that the last twenty years could have been very different if I or someone else had thought to check my pulse and blood pressure. PoTS can’t be cured but it can be managed with compression clothing, and increasing salt and fluids. Salt thickens your blood volume, squeezes the blood back to your brain.

What a refreshing slap in the face to realise that something so apparently mysterious and integral to a sense of self has such a simple treatment. I also read In Search of Lost Time this year, and all the way through couldn’t help thinking ok, the read of my life, but what if someone had simply given Proust ventolin ...

George MacBeth

In early August—running late to meet friends for cocktails I probably couldn’t afford, distracted, overworked, underpaid, and somewhat emotionally contorted—I tripped and fell into the gap between the Sonnenallee S-Bahn platform and the approaching train. This slammed the kibosh on my summer plans. So for the next month and a bit, laid up on the sofa in my friend’s swanky first floor apartment (my own on the fifth having now become pretty unreachable), I suddenly had a lot of time spare for watching. Like Bart Simpson in “The Bart of Darkness,” or Jimmy Stewart in Rear Window, being unable to go out and actually participate in the late, lake summer larks made me both immensely sulky and rather scopohiliac. My screen-time spiked precipitously; I hobbled on crutches around the palatial Altbau, stationing myself on chairs by the apartment’s numerous high, street-facing windows to gawp out at Potsdamer Straße; and I watched a frankly unhealthy number of films.

Of all these films it was Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s About Dry Grasses (2023) that most endured. Watching this utterly destroyed me. It hammered decisively against something evidently brittle and ripe for destruction inside, until it crumbled into a fine powder (figuratively speaking—fortunately no further skeletal damage). In what otherwise felt like a pretty lacklustre and uninspiring year for film, Ceylan’s slowburn drama about Samet, a disenchanted and world-historically conceited high school teacher (and amateur photographer) enduring a misconduct trial in a desolate outpost of rural Anatolia, came as a welcome reminder of everything I knew but had perhaps forgotten cinema can be and do. Though unashamedly novelistic in its moral and philosophical tenor, About Dry Grasses took bold formal risks at key junctures, and continually sought out fresh yet not gimmicky ways to intensify and modulate its themes.

I began to wonder what abstinent regimen could have allowed Ceylan to produce such a film in 2024. There is one scene in particular, where the quietist cynicism of Ceylan’s anti-hero is suddenly brought under scrutiny on a dinner date with a more idealistic local teacher Nuray, in which I felt the filmmaker’s sheer assurance and control had sent him into an orbit far beyond any of his peers. It is a film that fully scrutinises the psychic benefits tied up in postures of distance and of disengagement, and raises genuinely troubling questions about commitment, self-protection, and keeping the world out—only to leave them all in abeyance and its protagonist fundamentally unchanged.

Heather McCalden

One night in July, during a heatwave, I went to an immersive theatre performance set in a five-story warehouse. An elevator deposited me on the top floor where the light was so dim it blurred the entire environment, and my state of mind. I had the sense that somewhere, just out of sight, was a leaky faucet dripping one slow drop at a time into a metal sink, though I’m not sure why I thought this. The space seemed to have an echo ricochetting across its tiled walls, but it never quite materialized into a specific sound. As my eyes adjusted, I wandered through a maze of rooms, all clinical in nature. I was in a hospital, or possibly an asylum. The décor indicated the 1930s and my instinct was not to touch anything; beads of moisture covered bed frames, mirrors, and exposed pipes, as if the set itself was perspiring. Eventually I came to what could only be described as an operating theatre, with four or five audience members stood in a semi-circle behind an operating table. On the other side of it was a nurse performing a dance solo as sharp and precise as a knife. At its conclusion, I slowly realized the nurse was staring straight at me, but before I fully grasped this, she had my hand and was using it to pull me down a narrow corridor.

We ended up in a tight, rectangular office equipped with an army cot. The door closed behind us. Between the heat and the eeriness of the situation, I just accepted what was happening. Something had sweat through the theatricality and into reality, and everything began to feel… unstable. Wordlessly, the nurse arranged me on to the cot, pressing my shoulders down and extending each of my legs until I was prone. For a split second, she turned her back towards me, and her shadow spread monstrously across the walls. From a compartment she withdrew a wool blanket and proceeded to cover me with it, systematically tucking in all the edges until I was sealed in a cocoon. Her face was so near my own as she did this, I felt the debris of COVID loosen in my memory. I stopped breathing.

Then, abruptly, the nurse stood up, opened her mouth, and extracted from it a long, tarnished screw. She held it delicately in the air for a few moments as if it were a tooth, or a diamond. “Don’t tell anyone,” she whispered, before fleeing the scene. But, there was no one to tell. This was the closest I had been to anyone in months.

Jacob Bard-Rosenberg

(Collage by Jacob)

Jade Jollivet

It’s February 4th but 40 degrees, it's 10.30pm but bright as a sunrise in the Sambodrome Marquês-de-Sapucaí. The carnival hasn’t started yet but the stadium is already paved with a fantasy of feathers, glittery bodies, coloured music instruments and tanned and oily swaying hips.

In a week, star samba schools will parade one after another, from 8pm until the early morning during four long consecutive nights, from one end of the 700-meter long stadium to the other. An exercise in endurance for Cariocas dancers and musicians, who prepared for a year to present their magnificent show to the jury, grading, among others, harmony and fancy.

But tonight, they are rehearsing, without the final costumes and floats, in front of their audience, the ones they live with in the favelas. The ones who sing the lyrics and know the dance steps. The ones who helped to weave the skirts and the corsets, the families of the drummers and the friends of the march leaders.

In a week, the ticket will cost up to $300, in a country where the average wage is $220, thus excluding many Brazilians from attending. In a week, the monstrous social inequalities of Rio de Janeiro and the failure of the multicultural socialism will be played again on this ground, and the performers will compete among themselves.

But tonight is competition free, and the sambodrome is open to all. It’s full as an egg and I am here too, part of this 90,000-people crowd. I am attending a party to which I was not invited but was nevertheless welcomed. Tonight I am contemplating the infinite poetry of the togetherness and I am moved as I never was before. Harmony and fancy are forever.

(Photo of Rio carnival by Jade)

Over the last few years I became obsessed with the fiction and criticism of Gary Indiana. He passed away a week ago at the age of 74. Getting to grips with his body of work was like discovering a new tonal sequence in music for me. It allowed me to think about what sentences can do in a way that made reading exciting again. I never him, sadly, and my condolences to all those who knew him.

I’d been building up to writing something about him, be that a book chapter or an essay, slowly, with nothing really fomenting aside from excessive notes and lists of quotations. Hastened by his death last week, Orlando Reade and Chris Page invited me to write a tribute for Effects Journal. And so I did. There’s much I could have said, and still want to. The essay titled is intended to make Alicia Keys’ voice bleed in your ear.

Indiana’s work was singular, brutal, and very fucking funny. I tried to describe it in an email to a friend in May 2023 and did so as follows:

“Your drawing of the connection between Eliot and Wordsworth in particular got me thinking about something that novels perhaps can do that poetry cannot always do so easily in terms of the disenchantment of psychic and social reality.

The last few years I've been working through the oeuvre of Gary Indiana, a lesser-known associate of Kathy Acker, Dennis Cooper and Brett Easton Ellis (and a superior writer to all three). A friend introduced me to his novels and he is, perhaps, the most interesting living prose fiction writer that I have stumbled across. His work is cruel, scathing, inexhaustible and brutally funny. He has many targets, but perhaps his most common one is the embodiments of the American bourgeoisie in its cultural formations since the late 80s onward, in the aftermath of Reaganism and with the excessive wealth and spending power that they accumulated in the 90s (most of his novels were written before 9/11, too).

In his crime trilogy: Resentment, Three Month Fever, Depraved Indifference, each novel takes up a well-known murder case that became a mass media spectacle (respectively: the Menendez brothers, Andrew Cunanan's murder of Gianni Versace, Sante and Kenneth Kimes). You can tell that Indiana has done extensive research into these cases as well as their place in the national psyche (I think with TMF he actually looked at the police records about Andrew Cunanan). What he does in these novels is very carefully make explicit the constant dependency of bourgeois wealth, the grotesque excess of consumption and (to draw in your beautiful reading of Klein) the kinds of idealisation that the pursuit of it requires, and the way that the idealisation occurring within these damaged and disgusting subjects functions as a way of blinding them to the extreme perversion of their interpersonal actions, resulting in each novel in an act of murder.

What I find particularly impressive is the way that Indiana manages to inhabit the thought patterns and processes of the most damaged and violent bourgeois subjects, while the lives that they lead are defined by chintzy glamour and excessive wealth, and push the relation between inner psyche and worldly existence to a climactic end – in what is a heavily fictionalised narrative.

The way that the novels balance inner and outer reality is so careful in the crime trilogy as to be barely perceptible. I think the novels are a kind of stylistic nihilism exactly as Jacobi accuses the work of Fichte as containing, there is no transcendence, no God, no salvation, only the brute cruelty of the world. There is another manoeuvre that happens within the humour of his work but I haven't, yet, found a language in which to pin it down.

Certainly, the enjoyment of the novels is that they are bleakly funny. I've attached a passage from Depraved Indifference that briefly slips into the perspective of an Argentine housekeeper of one of the bourgeois brutes. It doesn't necessarily illustrate the element of Indiana's work that I'm describing but it certainly illustrates something about the sharp extremity of his style.”

Funnily enough, lots of these thoughts found their way into the essay. A testament to the importance at correspondence. Even though I’m shit at it (apologies if I owe you an email).

(Gary Indiana with Hilton Als in the late 80s)

For Plinth I wrote about Victor Boullet’s exhibition of paintings at The Artist Room in Soho. It’s now in its last week. I thought it was great. Boullet also messaged me and said he liked the piece, which was nice. I also wrote about the last Yorgos Lanthimos movie, which I hated. He’s a hack when he’s trying to be smart. But Poor Things was good because he’s good at stupidity.

Chino Amobi has finally released a follow-up to Paradiso, his 2017 record that I think is one of the best pieces of contemporary music. You can listen to Eroica on bandacamp.

The title of this post is taken from Clinical Wasteman’s response to my Gary Indiana essay on the rotting corpse of Twitter. Check out his music in the stellar Triple Negative. He once co-wrote this essay on childhood that I think is brilliant.

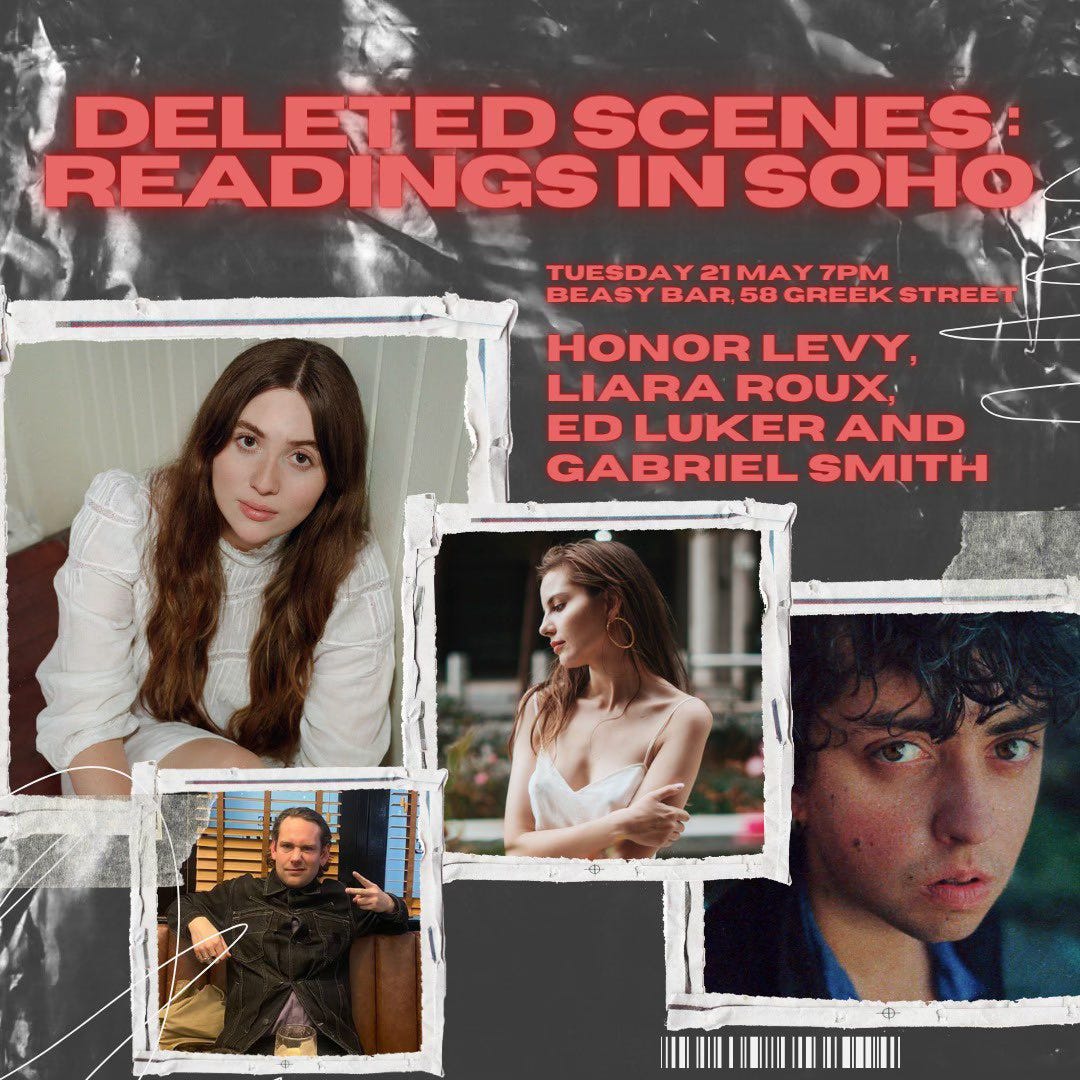

A joyous Friday to you, dear readers. In lieu of a longer post, this is a little update on what I’ve been up to and an announcement of a reading.

I spent a strange nine days in Berlin coming to terms with the loss of a wonderful person who I lived with when I first moved to London. I found out about Marina’s passing in a pool hall on Green Lanes at 1am after doing a reading (an excellent MAP fundraiser organised by Tom Willis, Maia Bear, and Matthew Holman). Not the best time. But there never is. Grief is the strange and continuous weight of being overwhelmed, like being bashed around by a heavy tide when you’re not quite ready to swim.

I barely had time to process it. And then, two days later, in Neukolln the news hit me like a bottle of sterni round the back of the head. I wrote a little about it here for Curatorial Affairs. Thanks to Jacob for asking me, and the most recent piece up on the blog, an interview with Jack Self, also looks fascinating.

Wednesday night my old friend Tom gifted me with a ticket to see Clarissa Connelly at Kings Place. It was honestly one of the most exceptional performances I’ve seen in a long time. I loved how her compositions, their structural complexity, came to life amplified on stage. There was a strangely coherent genre hopping from the ecclesiastical choral work, to the prog time-signatures, and 90s post-shoegaze guitar dirges. She also has an absolutely phenomenal set of pipes on her, something that comes across with even more oomf on stage. Check out the new record World of Work.

I’ve been very mentally distracted the last few weeks, for a bunch of reasons. But I’ve been very slowly reading Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming-Pool Library, having devoured Line of Beauty last month in about 5 days. I’d like to write more about why I’m so taken with Hollinghurst’s gratuitous portraits of upper-class London. I think it’s a lot to do with his tone. He gives such rich detail to the rich, their indulgences, obsessions and proclivities, that it is both loving and medically cruel (it reminds me a little, in this respect, of the films of Todd Haynes). That capacious approach seems to me much more honest than the fish-in-the-barrel class war stupidity of, say, Triangle of Sadness type of cultural affairs.

On Tuesday I’m reading from the creative project that has consumed my last few years: my novel-in-progress, Educated Pains, for Pavlos, the most fun promoter in all of London with some perhaps familiar names of literary-upstarts.

Here’s a little precis of the project:

In the wake of his father’s death, Thomas Muckle gazes at Stromboli while forest fires rage along the coast of Calabria, trapped in his conflicting desires. What’s more, he needs to paint ahead of his solo show.

Back in New York, an unexpected guest and a Faustian bargain revive his fortunes and ruin his relationships.

A novel about desire, grief, and the fear of wasting your life in the grander contexts of political and climate crises, Educated Pains asks how much would you compromise your principles to relieve your anxieties? It looks at the ways we try and fail to love, create, and live, and the toll it takes on those around us.

Bluntly, I’m looking for an agent to represent the project, so if you know any good ones, send them to the reading.

Come and say hello on Tuesday.

Loading more posts…