"C'mere" — a tribute to Bernadette Mayer

The poet Bernadette Mayer is dead. I am going through a break up. I go to airdrop this photo of the Mayer poem to my laptop and the first suggestion is that I send the poem to my former beloved.

“C’mere,” Mayer wrote, and now she’s gone. But the instructions and demands are still there in all her poems, jumping around in linguistic animation and all its beautiful mechanics of presence and distance: You’re here and I’m there. You’re there with him and her, and I’m not, but I will be, if I could just, or if you could just. But it’s not quite, but it could be, and maybe it will be soon. And I remember that it once was, just yesterday in fact.

Love, there are many ways to love, so many people to love and even to hate, and the poet Juliana Spahr said that Bernadette Mayer’s sonnets were more about intimacy than desire, because intimacy speaks to the difficulties and pleasure of love’s presence, rather than its fantastical absence.

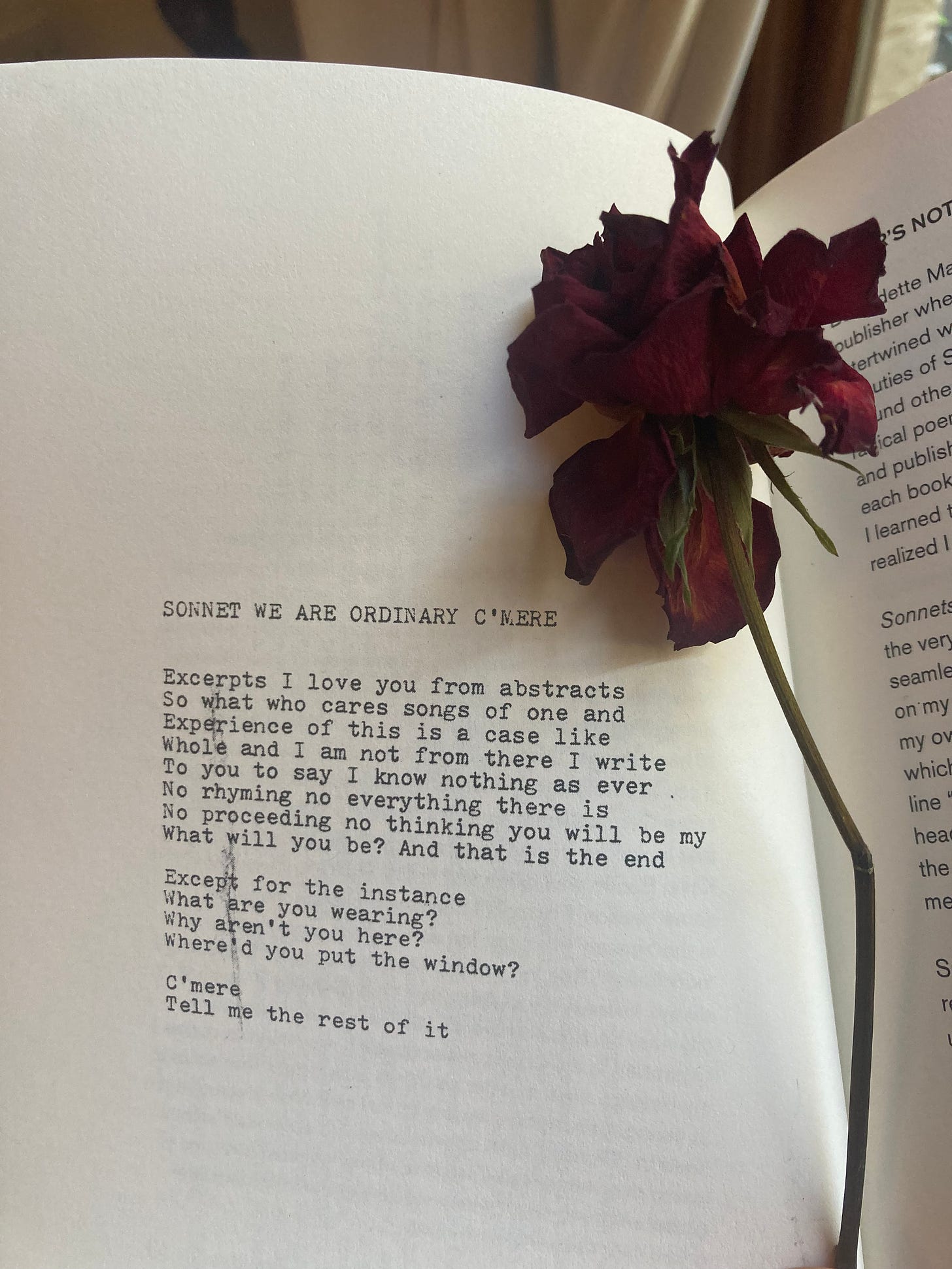

Out of print for many years because it is so popular, I bought my copy of Mayer’s Sonnets for too much money because I wanted to get closer to the pleasure and difficulty of the work’s presence, on the page rather than the screen, having read the poems for years on a crummy, distant PDF. It’s one of the books of poetry that I return to most often, and a possession that I covet.

How funny to covet a book where the poems poke fun at the strangeness of intimacy and possession and relation? It is useful to have poetry reflect our failings and the humour of those failings back to us. Bernadette Mayer loved to make fun of herself and her readers for our persistence in wishing to find something that constantly evaded us, while being surrounded by things that did give us life and pleasure and enjoyment while not noticing them.

During lockdown (ugh, dread), I would have baths of an hour or two in length, my skin soaked in the presence of the water while my friends and lovers were absent. I would speak on the phone for hours, surrounded by candles, eating an orange and drinking green tea. I would leave voicenotes to my dearest of a single poem from the Sonnets, frustrated by all the distance, finding comfort in their humour and play. The telephone, and the voicenote, is such a great way to play with intimacy and presence in absence, the way it sits between public and private, opening up all the thresholds.

How do poems help us to love? I loved teaching Mayer poems in poetry clases, sharing them with people for the first time, because it was hard for people to have responses to them beyond enjoyment and confusion. They would say that they really enjoyed the poems but really struggle to translate that enjoyment into any kind of proposition or description of the work. Over time people would tell me that visceral feeling of enjoyment and frustration would develop into love, but all at language's edges, yet through language — where rationality strains to know why it loves. And that’s what love itself is like, no? It is the compulsion to continue and to feel, to just enjoy presence, against your rational self.

Our desire for intimacy and connection are so partial, and the best poetry can intimate the full feeling of those boundaries as a kind of extra-rational sense. That was what made Bernadette Mayer’s poetry so joyous. And in that sense her poetry will live on forever with its reading and rereading because it is so present to its own presence, if that doesn’t sound too mystical. I will love reading your work that you left behind Bernadette, because you believed in the possibility that poems could be forever, and that forever was always now, and you knew that now was often wounded, difficult, and painful. And you still wanted to find something there, something that could help move us somewhere else: come here, or c’mere.

Leave someone you love a voicenote of you reading a Bernadette Mayer sonnet. Do it right now.